Dark Ages of Mining industry

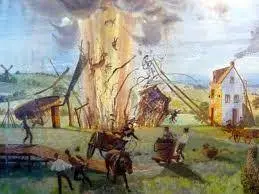

Hello everyone and welcome to the another article on Explosion Proof Lighting. Today we will explore the origin of Explosion Proof Lighting. It started long back ago around 200 years ago in the early 19th centuries. When coal mining industry in Europe was flourishing. So as the industrial revolution got underway and miners started penetrating deeper and deeper into the earth in search of coal to feed the demands of British industry. The rate of accidents soared and indeed between 1807 and 1812 an estimated 300 miners are thought to have died in fire damp related accidents and one of the worst of these disasters was called the Felling Mine disaster and this occurred on may 25th 1812 in new castle. Upon time and it resulted in the deaths of 91 miners, and this is really the accident that spurred people to action to find some sort of solution for this problem of fire damp in the form of a lamp that would not ignite the gas and lead to explosions.

on may 25th 1812 in new castle. Upon time and it resulted in the deaths of 91 miners, and this is really the accident that spurred people to action to find some sort of solution for this problem of fire damp in the form of a lamp that would not ignite the gas and lead to explosions.

The reasons of explosion in mining industry

Now as you can imagine coal mining is a very unpleasant and very dangerous occupation. There are a whole host of dangers that you can encounter underground including cave-ins accidents with explosives and other tools. It’s a very hot airless low oxygen environment, and the constant presence of coal dust in the air makes miners very susceptible to long-term respiratory illnesses such as black lung disease. But traditionally one of the greatest and most feared dangers down into mine shaft was something called damp. And this doesn’t refer to dampness or wetness as we would think of it today, but rather to a series of asphyxiating and explosive gases that were produced by the rocks in a coal mine, and the term derives from the German word ‘Dampf’ which means vapors.

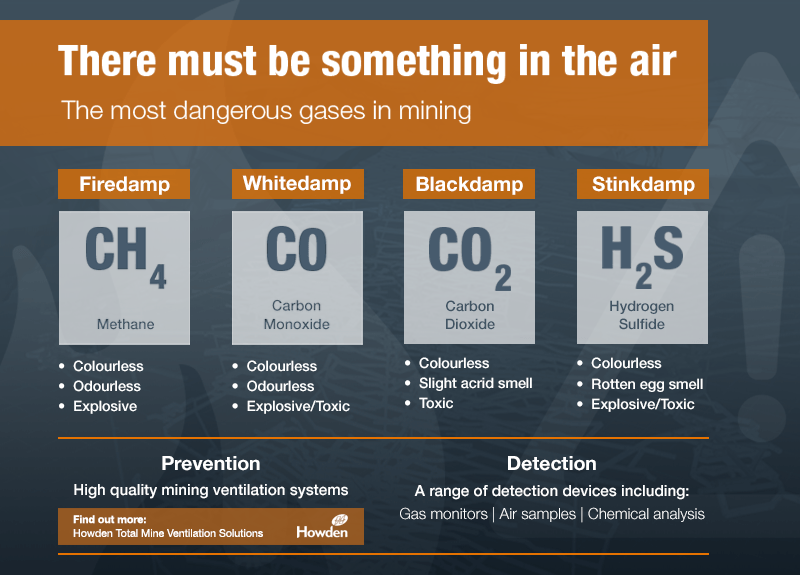

There were a number of different kinds of damp and they all had very colorful names given to them by the miners for example there was Black damp also known as choke damp or stiff. This is a mixture of Nitrogen, Carbon dioxide and Water vapor that was actually given off by the coal itself as soon as coal is exposed it starts to absorb air and give off Black damp and this could accumulate in a mine and cause respiratory problems and consciousness death.

There is also White damp which is Carbon monoxide and this is one of the most insidious of the gases because it’s odorless, it’s tasteless, it’s colorless and it actually preferentially binds to hemoglobin in the blood, and thus replaces oxygen and essentially suffocates you from the inside out and you never feel any symptoms until you start passing out.

There’s also After damp this is a mixture of Nitrogen, Carbon dioxide and Carbon monoxide which is produced by the combustion of coal dust or of fire damp which we’ll get to in a second. So when there was an explosion even after the explosion was over, the danger wasn’t over because it sucked all the oxygen out of the mine and left behind asphyxiating gases, that could still produce a lot of damage.

There was Stink damp which was hydrogen sulfide which is both explosive and highly toxic. But thankfully in that case hydrogen sulfide is very readily detectable by its strong order of rotten eggs even at very small concentrations. So it was very easy for miners to determine that there is a Stink damp leak before the concentrations got up to lethal levels.

And finally you have Fire damp which is typically methane could also be hydrogen and this is a gas that burns or explodes. This is a particular danger in the 18th and the 19th centuries because of miners work by the light of naked flames they would carry Oil Lanterns or often Candles on their hats and if they encountered flammable gas then it would ignite and cause an explosion.

The Call for Illumination: Early Attempts

A key supporter in this effort was Reverend John Hodgson, who led one of the initial safety committees aimed at addressing this issue. Unfortunately, this committee didn’t take significant action.

A key supporter in this effort was Reverend John Hodgson, who led one of the initial safety committees aimed at addressing this issue. Unfortunately, this committee didn’t take significant action.

it dithered for quite a while until in 1813 there was another disaster at Felling and finally they were spurred into action.

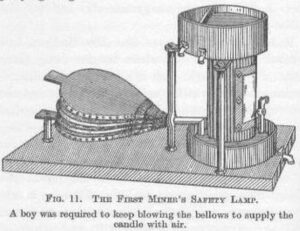

Now the first person to have a go at coming up with a solution was a gentleman named William Reed Clanny. He was an Irish physician who had treated a lot of victims of various mining disasters, and his solution was to isolate the flame from the outside environment through the use of a water trap sort of like the water trap that stops sewer gas from backing up into your toilet now. Because of this water trap in order to supply oxygen to the lamp. The lamp had to be fitted with a bellows that had to be operated at all times so this turned out to be not a great solution.

Because down in a mine nobody has the time to be constantly pumping the bellows on a lamp. Everybody has to be digging because you’re paid by the ton of coal that you extract also they found that even if a little bit of fire damp got into the lamp it would instantly extinguish itself. So not a very practical solution but it was at least an early attempt.

George Stevenson's Safety Lamp

So the next person to have a go at coming up with a solution was an engineer named George Stevenson, who later became famous for developing one of the first steam locomotives. At the time he was just a mining engineer at the Killingworth Colliery, and the design he came up with was based on the observation that flames don’t travel very easily through narrow tubes so his lamp took in air through a series of capillary tubes in the bottom and then the exhaust from the lamp itself was passed up through a tall glass chimney to a plate covered in small holes and the idea was that by slowing down by metering the rate of gas flow through the lantern you can make sure that any damp that got in wouldn’t be mixed with sufficient oxygen in order to create a flame and to propagate that flame out into the outside environment and when he tested this out in his mind it seemed to work pretty well unfortunately for him he didn’t realize that at the time the safety committee organized by reverend Hodgson had already asked someone else to come up with a solution to the fire damp problem.

So the next person to have a go at coming up with a solution was an engineer named George Stevenson, who later became famous for developing one of the first steam locomotives. At the time he was just a mining engineer at the Killingworth Colliery, and the design he came up with was based on the observation that flames don’t travel very easily through narrow tubes so his lamp took in air through a series of capillary tubes in the bottom and then the exhaust from the lamp itself was passed up through a tall glass chimney to a plate covered in small holes and the idea was that by slowing down by metering the rate of gas flow through the lantern you can make sure that any damp that got in wouldn’t be mixed with sufficient oxygen in order to create a flame and to propagate that flame out into the outside environment and when he tested this out in his mind it seemed to work pretty well unfortunately for him he didn’t realize that at the time the safety committee organized by reverend Hodgson had already asked someone else to come up with a solution to the fire damp problem.

First Safety Lamp : Davy's Lamp

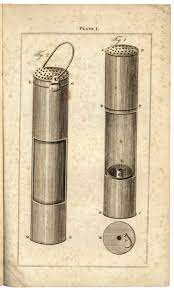

However, the spotlight was stolen by Sir Humphry Davy, a brilliant chemist. In a period of feverish work lasting from October to December 1815, Davey conducted a number of experiments and came up with a prototype safety lamp. So Davey’s design was actually quite simple it was an ordinary oil lamp but with a tall cylindrical chimney made out of a double layer of steel mesh. And how this works is that while oxygen and fire dam can penetrate through the mesh and reach the flame if that fire damp ignites the flame front can’t propagate back out through the mesh. This is because as the flame passes through the mesh the metal in the master jacks the heat sink wicks away all the heat from the flame which lowers the gas below its auto ignition temperature and snuffs out the flame and thus preventing the flame from propagating through and igniting any fire damp that might be outside the lamp. So the mesh serves as a very crude form of flame arrestor which is a type of device that’s often used in say natural gas pipelines or other applications where you’re trying to transfer large amounts of flammable gas and where the propagation of a flame through the whole system would be disastrous.

However, the spotlight was stolen by Sir Humphry Davy, a brilliant chemist. In a period of feverish work lasting from October to December 1815, Davey conducted a number of experiments and came up with a prototype safety lamp. So Davey’s design was actually quite simple it was an ordinary oil lamp but with a tall cylindrical chimney made out of a double layer of steel mesh. And how this works is that while oxygen and fire dam can penetrate through the mesh and reach the flame if that fire damp ignites the flame front can’t propagate back out through the mesh. This is because as the flame passes through the mesh the metal in the master jacks the heat sink wicks away all the heat from the flame which lowers the gas below its auto ignition temperature and snuffs out the flame and thus preventing the flame from propagating through and igniting any fire damp that might be outside the lamp. So the mesh serves as a very crude form of flame arrestor which is a type of device that’s often used in say natural gas pipelines or other applications where you’re trying to transfer large amounts of flammable gas and where the propagation of a flame through the whole system would be disastrous.

Davey presented his design at the royal society on January 25th 1816, and later that month it was tested in an actual coal mine and found to work quite well. So it was approved for mass production and adoption. Davy never took out a patent on the lamp, he offered it for free to be used to improve the safety of coal mining.

Rivarly Between Davy and Stevenson

Unfortunately, shortly thereafter a bitter dispute erupted between Stevenson and Davey, over who invented the safety lamp and whose design worked better this really broke down along class lines. According to Davey, Stevenson was merely a lowly mechanic an uneducated engineer, he’d come up with his design by accident through trial and error, whereas he Davey was a proper scientist he had come up with his design by a sound scientific principles and careful experimentation. But in reality both lamps work essentially the same way, the capillary tubes in Stevenson’s design worked exactly the same way as the steel mesh screens in Davy’s. Although, Davey was awarded the Rumford medal he was ordered a prize of 2000 pounds for his contributions and made a full member of the royal society. However, Stevenson was awarded a paltry 200 pounds and this so incensed the mining communities of northern England that they put together a collection a subscription and raised a thousand pounds to give to Stevenson.

The result of all of this was that Stevenson’s lamp which became known as the Geordie lamp was used almost exclusively in the north of England whereas Davey’s lamp was used almost exclusively in the south.

Drawbacks of Davy's and Stevenson's safety lamp

Despite the intense rivalry that persisted for years between these men, their solutions were never entirely adequate under actual mining conditions. Stevenson’s lamp for example was prone to breakage because of the glass chimney. This was alleviated somewhat by the addition of a perforated metal cover but this limited the amount of light that was actually cast.

Meanwhile Davy’s lamp because of the double layer of metal mesh produced a very inadequate light. Miners really didn’t like it and they would prefer to use a much brighter light like a regular lamp or a candle even if that came with the increased risk of a fire damp explosion.

And they really had to be coerced into using the new Davey’s lamps though both lamps proved incredibly successful as means of detecting leaks of fire damp because if it sucked in fire damp through the mesh or through the capillary tubes the flame would develop this blue cap as it burned off the methane, and the height of the flame it could be used to gauge the amount the concentration of fire damp in the mine. And a lot of these lamps were specifically made for this purpose and they had graduated markings on the outside to measure the height of the flame and tell you how much fire damp there was. Whether it posed a risk of explosion so both the Geordie lamp and the Davy’s lamp would be used for many years in their original forms.

Improved Design

Until 1839 when our old friend William Clanny came up with a new version of the miner safety lamp that incorporated design details from both Davy’s and Stevenson’s lamps so in a Clanny’s lamp the screen from Davey’s lamp is moved from around the flame to up top where it forms a sort of cap whereas the flame is now surrounded by a glass screen as in Stevenson’s design. So in its new position the screen serves the exact same purpose as it did before as a flame arrester however by surrounding the flame with a glass screen it improves the amount of light actually cast by the lamp making it a lot more useful than the earlier designs.

Until 1839 when our old friend William Clanny came up with a new version of the miner safety lamp that incorporated design details from both Davy’s and Stevenson’s lamps so in a Clanny’s lamp the screen from Davey’s lamp is moved from around the flame to up top where it forms a sort of cap whereas the flame is now surrounded by a glass screen as in Stevenson’s design. So in its new position the screen serves the exact same purpose as it did before as a flame arrester however by surrounding the flame with a glass screen it improves the amount of light actually cast by the lamp making it a lot more useful than the earlier designs.

now the next year an inventor named Matthew Muesler would come up with a slight improvement where he shaped the screen cap into a short cone and this improved flow and helped improve the brightness of the lamp and finally in 1882 a French inventor named Jean Marceau would come up with the final improvement to the overall design which was the addition of this chimney or bonnet which again improved airflow through the lamp and also protected this screen from being damaged it made the whole lamp a lot more robust. And this is the form that the miner safety lamp would maintain well into the 20th century. They actually wouldn’t stop using this until around the 1930s long after electric lighting had become standard in coal mines and they weren’t really used for lighting at that point. They were mainly used as detectors for various kinds of damp so not only fire damp but also choke damp and other asphyxiating gases. For example Carbon dioxide will put out a lamp or a candle flame at concentrations far lower than it would be dangerous for humans. So it serves as a great early warning of high carbon dioxide concentrations and thus the lamp serves the same function as the traditional canary in a coal mine.

So there you have it a brief history of the minor safety lamp a key innovation that helped spur on the industrial revolution and helped make coal mining just a little bit less dangerous of an occupation.

Contact Information:

- Website: sensor-control.ae

- Email: sales@sensor-control.ae

- Phone: +971502447100